THE FOUNDATION OF MEMORY

After my mother died, I discovered some random photos tucked away in her desk. A small packet of memories carefully wrapped in an envelope worn soft from frequent use, with a little bit of cardboard to keep them flat, they were photographs of my late stepfather’s family. Gerhard kept them handy in case anyone thought to ask him about his relatives. Even now, all these years later, I can recall his long elegant fingers … gnarled from years of hard work … sorting through them like rosary beads. He had emigrated from Germany as a teenager after the second world war, leaving behind the remains of his family. I suppose the photos are of his younger brothers and sisters, a visual record of the life they lived in post-war Germany. But the photos could equally be those he brought with him when he left. They could be of his parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles lost to the war and remembered only faintly. I have no way of knowing. The narrative of the images died with him.

In one of the photos, his family have gathered to make a visual record of some special day. They stand arm in arm, sending happy greetings to those that can’t be there to share in the occasion. Ever vigilant, mothers and aunts and grandmothers have kept the children looking starched and tidy. There is also a lovely image of a grandfather with a very small blond cherub, and another of the same cherub with her mother … although the image might well be of an unrelated blond toddler from an entirely different event. Certainly, there are photos from other times and places, saved to bring back memories and to share with absent friends and family. There are starchy aunts, happy newlyweds, lovely brides, darling babies, and young men in stiff collars. They are all blond and carry themselves with distinction … except perhaps the babies. And sadly, I have no idea who any of them are.

The photographs serve as a poignant reminder of how bereft he must have felt, living so far from his homeland. Granted he had led a rich life here, but his roots and his family history were always at a distance. His memory is most likely better kept by his family in Germany than those of us who knew him here, because he has always been a part of his German family’s narrative. He is one of their own. Whereas here, he was known to us as my mother’s second husband. And while we loved him, and he was a happy part of our family, his history was written in a foreign language.

And now, just like Gerhard seventy years ago, millions of refugees are leaving their homeland behind and will, of necessity replace their family with photographs and letters. It might be their phones and their computers that keep them connected, but just like Gerhard, in the end they too will be added to the bereaved, buried by distance from their pasts. They too will learn to live in a foreign language with static images of their past to keep them company.

Certainly, in this day and age the ability to share our lives using photographs and videos is beyond our capacity to comprehend. However, our memories are constructed of more than visual images. A fuzzy black and white image from Gerhard’s envelope of memories tells me nothing I need to know. Who are the people standing together? What are their names? Why are they gathered together? Where are they? When was the picture taken? Let’s face it, all those images saved to record our lives are meaningless without the stories to go with them. There are not enough hours in the day to narrate all we record, and yet we persist.

We like to keep photographs of special times so as to be able to go back and re-live the day. And admittedly there is an urge to share happy times and important events with others. But once shared, all those images become deadweight … a concrete block of riches tied to our ankles. We keep the old albums and family photos to pass on to the next generation. However, unless the narrative has also been passed on, the images become ghosts, and the albums tombstones in a family plot where none come to pay their respects.

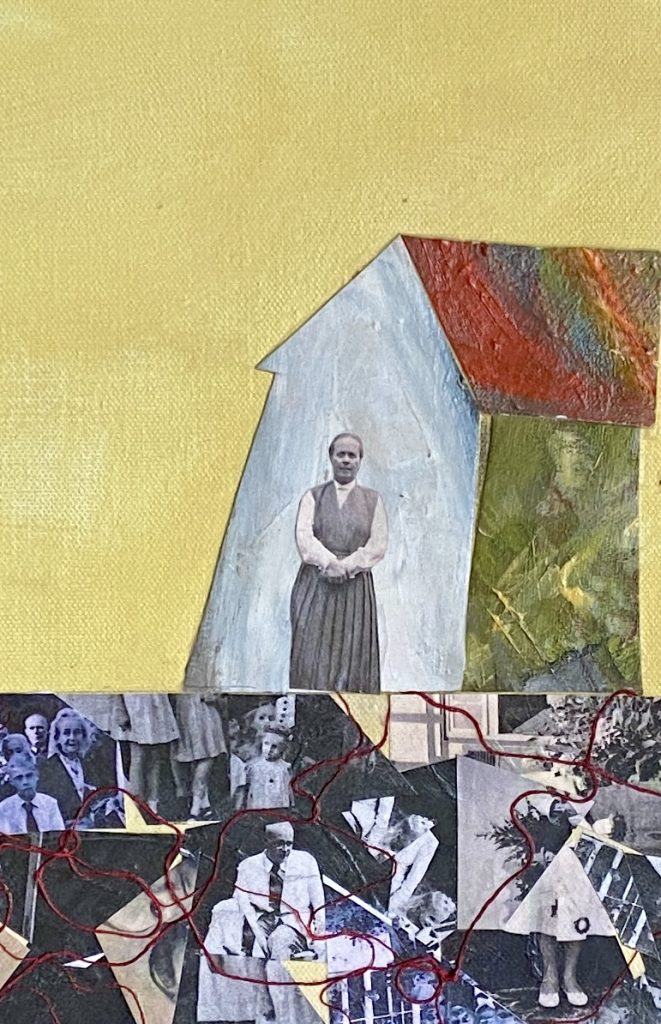

The latest of my mixed media works (above) is a reflection on the fate of these photographic ghosts. Here I have re-configured Gerhard’s family pictures. They have all been replicated and are shown here decomposing into the past, guarded by sentinels … the elderly aunts and cousins now themselves unremembered … enlisted to keep the family history alive. Bloodlines trace random patterns, but can draw no life from the composted imagery. Ironically in this imagined graveyard of photographs, traces of Gerhard’s family remain alive because I have used them to express how we feel when faced with someone else’s treasure trove of imagery. We know the photos were important to them, but the images are meaningless to those of us left behind to receive them. However, working with these images has resulted in Gerhard’s memories becoming braided into mine. But my story of him has nothing to do with his past, and everything to do with how little I really knew of his memories.

2 Replies to “THE FOUNDATION OF MEMORY”

Beautiful!

Wow Connie. Really wonderful.

Thought provoking. Such a fabulous job!